What are social rights?

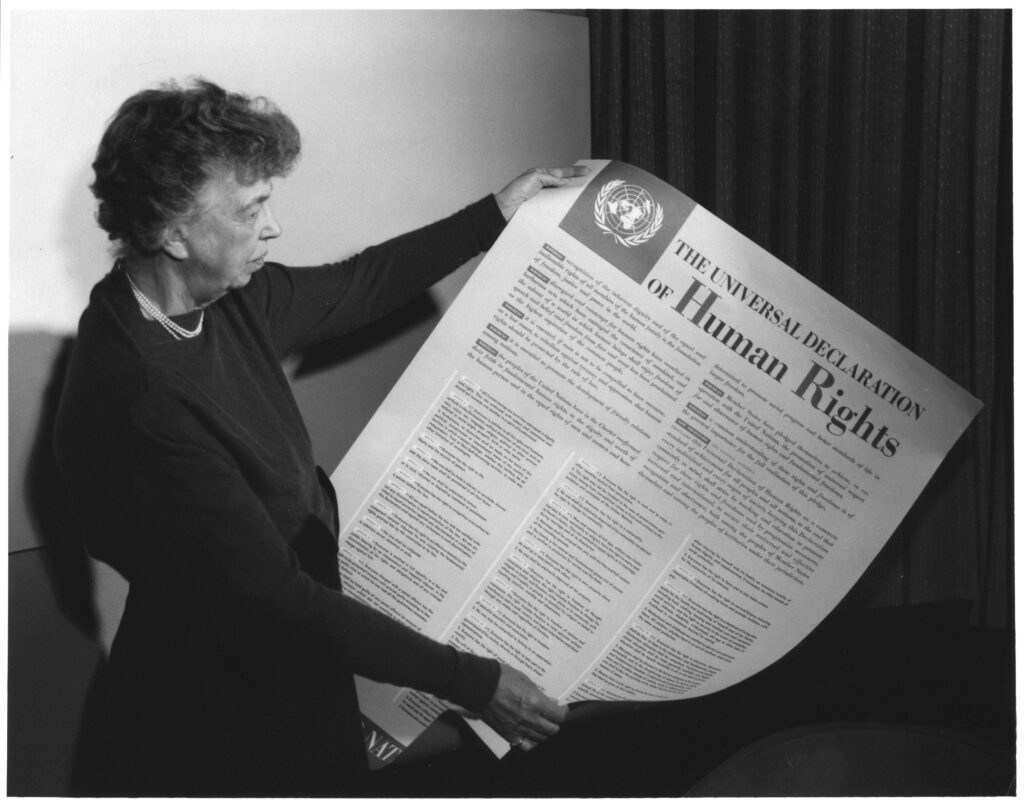

Social rights generally refer to the entitlements and protections which safeguard individuals’ well-being and quality of life. These rights encompass access to essential services such as education, healthcare, housing, and social security. They are supposed to ensure that all individuals can live with dignity and participate fully in society. Social rights have a long history, as societies have long debated the need for a ‘minimum’ that guarantees the dignity of any individual. Many social rights were enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) and later the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (1966).

This project is particularly interested in social rights related to work. These rights include the right to fair wages, safe and healthy working environments, reasonable working hours, and the ability to join trade unions. Concepts such as these, as well as protections for particular groups like women and children, are shaped by global norms, national laws, and local beliefs about work and the entitlements which work should provide.

Case Studies

This project is a comparative and interconnected study of global social rights in the decades following the Second World War. We have selected four geographic spaces with a shared colonial past, but offering distinct histories of labour activism and relationships to international capitalism. In each of the four case studies, we explore how social rights norms were developed and debated. We are especially interested in the global connections which informed these local discussions, and through which concepts of social rights were disseminated, adapted, and contested. We seek to untangle a worldwide network of people, ideas, and laws concerned with workers’ rights.

Germany

Germany was not unified under a single state until 1871, but soon became a pioneer in Europe for government welfare provision. In the 1880s, the conservative chancellor Otto von Bismarck introduced health and accident insurance, as well as a pension scheme. Despite Bismarck’s aim to undermine the popularity of left-wing politics, the Social Democratic Party of Germany became the biggest working-class party in Europe. They helped to enact social rights during Germany’s ill-fated first experience with fully democratic governance under the Weimar Republic (1919-1933). Trade unions were banned under National Socialism, but the Nazi regime adapted some of the labour movement’s rhetoric and symbolism to promise limited benefits for workers who were defined as ‘racially’ German. After 1945, two distinct German states emerged. In the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany), democratically elected governments maintained a ‘social market economy’, with welfare measures integrated into a capitalist system of enterprise. The socialist German Democratic Republic (East Germany) sought to mitigate popular dissatisfaction with economic stagnation and authoritarian conditions by guaranteeing a multitude of social rights. After the GDR’s collapse in 1990, the challenges of integrating the former East German regions into the structures of the Federal Republic have coincided with broader patterns of unemployment caused by deindustrialisation.

United Kingdom

Large-scale industrialisation took hold in Britain in the nineteenth century, and led to some of the earliest laws by a national government to regulate factory labour. Successive legislation restricted the employment of women and children and introduced health and safety provisions. After the Second World War, the expansion of pension provision through the 1946 National Insurance Act and the creation of the National Health Service in 1948 have come to be regarded by many as the cornerstones of the modern British welfare state. In other important areas of social rights, however, the state retained a rather minimal role compared to other European neighbours. Collective bargaining agreements between employers and employees, made without much government involvement, benefitted the more powerful trade unions but left casualised workers – including women and migrant workers – more vulnerable. Since the 1970s, the rapid decline of coal mining, steel manufacture, and shipbuilding has rendered Britain a particularly striking case of deindustrialisation in the Western world. The British Empire lost most of its territories after 1945, and the multifaceted legacies of imperial rule and decolonisation make Britain an important case study for a comparative and transnational project on global social rights.

Kenya

This East African territory was conquered by the British Empire in the 1890s, resulting in significant land seizures by white settlers. The area’s colonial history was shaped in large part by white settlers’ demands for a large, disciplined labour force of Africans whom they could fully control. Forced labour, terrible conditions, and coercive control, were the order of the day. Only after 1945 did the colonial state, under the leadership of a Labour government in Britain, start to reform this system significantly. These reforms sought to develop a ‘stabilised’ working class, disciplined and organised by apolitical trade unions. The reality was always more fractious, illustrated most overtly by the Mau Mau Uprising (1952-60) and the strike wave that accompanied the transition to independence, which was finally achieved in 1963. Unlike in neighbouring Tanzania, post-colonial Kenya, retained a capitalist economic system with a limited focus on redistribution, despite the prominent political positions given to trade unionists such as Tom Mboya.

Tanzania

Kenya’s larger southern neighbour is the product of a union between two colonial territories. The larger part, Tanganyika, was first seized by the German Empire in the late nineteenth century and became British only after the First World War. From then until independence, it was first a League of Nations Mandate and then a United Nations Trust Territory under continued British administration. To a significant extent, Tanganyika was an exemplar of the British policy of ‘Indirect Rule’, with colonial policies implemented through local Chiefs and ‘customary’ authorities. There was significantly less labour recruitment by white farmers than in Kenya, although similar ‘stabilisation’ policies took place after 1945. After the successful activism of an anti-colonial movement led by the charismatic Julius Nyerere, Tanganyika achieved independence in 1961. It merged in 1964 with the former Sultanate of Zanzibar, where an Arab ruling class had been overthrown by a socialist-inspired African-nationalist revolution. In the years that followed, after the Arusha Declaration of 1967, under Nyerere’s ideology of Ujamaa (familyhood), Tanzania would embark on an agrarian socialist experiment that would see mass resettlement of people into strictly regimented villages. Like other African states, from the late 1970s it was forced to reform its economy substantially as part of World Bank/IMF-ordered Structural Adjustment Programs.

Research Themes

Conceptions and Definitions of Work

What is work? A global and historical perspective complicates this otherwise seemingly straightforward question. Colonial governments, for example, did not see traditional African ways of life as fulfilling the requirements of productive labour and consequently authorised forced labour. Some forms of work which have commonly been carried out by women, whether in the household, tending to the family farm, or other non-remunerated forms of activity, continue to be held outside the formal sphere of ‘work’—withholding the rights this entails. Moreover, the definition of work shapes its opposite: unemployment. What does this mean in countries with a relatively small ‘formal’ economy? As we enter the age of the ‘gig economy’ with increasing casualisation, the question of who should have access to the full benefits associated with work now arises more widely across the globe.

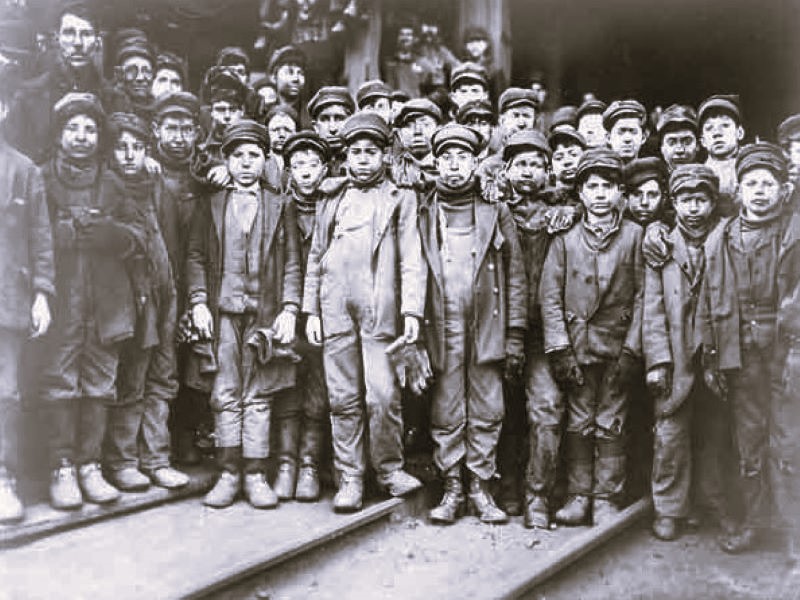

Children’s Labour

It is estimated that 218 million children around the world are engaged in unlawful child labour or legally permitted employment. Children’s labour has provoked fierce discussion ever since the nineteenth century. Should it be abolished as far as possible, removing any obstacles to — or distractions from — school attendance? Or should children have the right to work, if there is evidence that doing so under certain regulated conditions can benefit their development? These questions are not only relevant to the Global South, where poverty continues to be the driving factor behind child labour, but also to wealthier nations such as the United Kingdom, where most children have held a job by the age of sixteen. The socio-economic rights enjoyed by parents and guardians, as well as historically variable conceptions of what counts as ‘work’ and what constitutes a ‘child’, have influenced the manner and the extent to which children work.

Rights to Work, Fair Wages, and Collective Bargaining

A broad spectrum of specific rights for workers have been debated during the twentieth century, with discussions varying over time and between different geographies. Between 1945 and 1973, ‘full employment’ was a key public policy objective — but what did this mean within communities? Should there be a social minimum, and how can this be calculated? Should a male breadwinner be able to maintain a family on a single wage? And how should these levels of wages and conditions best be worked out: by government fiat or through a process for collective bargaining? These discussions, flowing through governments, trade unions, and international bodies like the ILO, shaped a global rights discourse caught between universal declarations and specific local conditions.

Older Workers

During the twentieth century, retirement — the transition from employment to a full withdrawal from paid labour — became possible in more prosperous regions of the world. With this breakthrough came debates as to how pensions should be funded and what benefits they should bring. Should state pensions be provided at a flat rate, ensuring a basic minimum to all recipients? Or should pensions reflect an individual’s income during their working life, and allow retirees to maintain their previous living standards? Our project also examines historical discourses surrounding the ‘right’ to remain in work. Although policymakers have frequently sought to encourage older workers to do so, employers have proven less keen to retain older staff. Nevertheless, in poorer regions with patchy pension systems, working into old age is a common reality, especially for unwaged labourers. Amid healthcare improvements and declining populations, discussions about the necessity and acceptability of old-age work have regained currency.

Health at Work

Considerations as to workers’ health inform many of the occupational rights which have been conferred and demanded in the modern era. Early laws to regulate factory labour sought to reduce accidents involving dangerous machinery. Yet other physical and mental health problems have generally received less attention in the workplace. Policymakers and employers have often been deterred by the alleged expense of health and safety measures, or proven unresponsive to concerns articulated by certain groups of workers. Employees, furthermore, have sometimes been reluctant to adopt practices which appear inconvenient or irrelevant to their needs. Despite the risks to health which work can pose, many politicians and healthcare professionals have contended that occupational activity benefits individuals physically and psychologically. The relationship between health and work has come under renewed scrutiny since the COVID-19 pandemic, as large numbers of older employees have taken early retirement and many individuals suffering from long COVID remain out of work.

Interviews

As part of our research into how work-related social rights have been conceived and expressed from the late nineteenth century to the present day, we will conduct around sixty interviews with policymakers, government officials, campaigners and members of the public. These interviews, to be made available on the UK Data Service, will shed light on understandings of social rights and ‘decent work’ across our four national case studies. If you would like to find out more about our interviews, please get in touch via our project email address: glosoc@sheffield.ac.uk.